FUENTE: EDX.ORG |

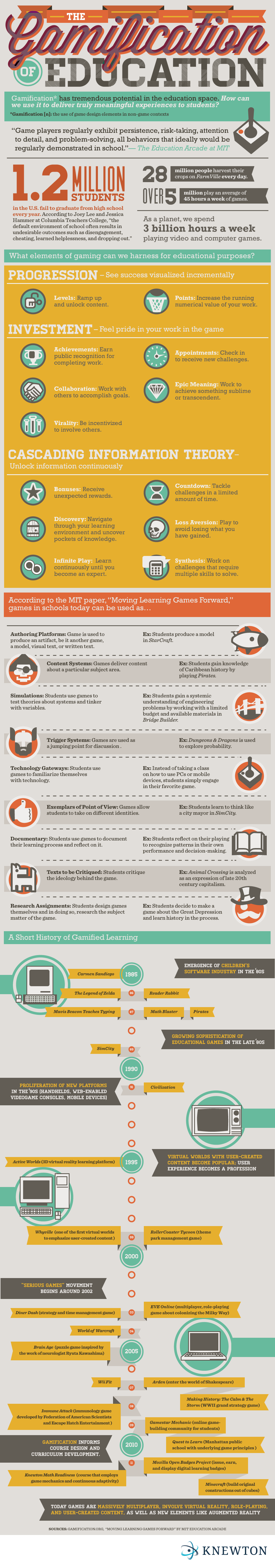

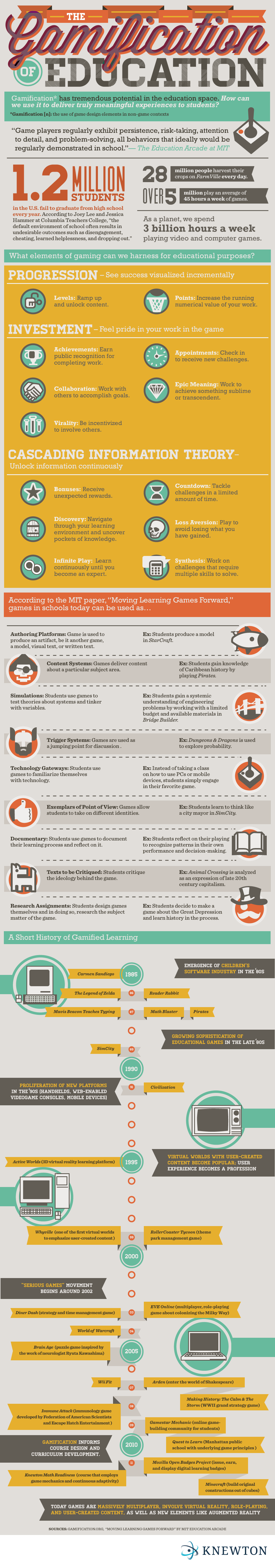

Educational software Knewton has produced a visually-appealing infographic on gamification: |

Tuesday, October 8, 2019

Gamification

PROJECT-BASED LEARNING

Getting Started With Project-Based Learning (Hint: Don’t Go Crazy)

A handful of tips to help teachers ease into PBL without getting overwhelmed.

August 6, 2012 Updated November 3, 2017

Are you just beginning with project-based learning? Are you concerned about time? Are you wondering about how to engage students in their first project? Anyone getting started with PBL has concerns and questions about making it a reality in their classroom.

One of the things we stress for new PBL practitioners is, as I say, “Don’t go crazy.” It’s easy to go too big when you first start with PBL. I’ve heard from many teachers new to PBL that a large, eight-week integrated project was a mistake. It was difficult to keep momentum, and students often grew tired of the project itself. Teachers and students both need to consider their own scaffolds and a gradual release to more long-term and complex PBL projects. Here are a few things to consider if you’re just getting started with PBL.

RENOVATE A PROJECT

Projects and project libraries are everywhere. Instead of planning a full project with all the learning targets, milestones, and products, teachers can save time by renovating an existing project.

As you search project libraries for ideas, remember to look at projects across all grade levels. Although you might want that very specific seventh-grade social studies project, you might find a relevant project in 11th grade that could be modified.

Be open to projects everywhere, find great ideas, and then modify.

LIMITED SCOPE

The longer the project, the more students should learn. Therefore, a four-week project will no doubt target many standards that must be taught and assessed, which can be quite daunting for a first project.

Try to focus on two or three priority standards for your first project. Concentrate the learning on one subject rather than multiple disciplines. And aim for a two- to three-week project, or approximately 10 to 15 contact hours.

In addition to limiting the time, you might consider narrowing choice. Instead of many product options, offer a short menu. Allow students to choose how they want to work, but choose the teams for the project yourself. There are many ways to build voice and choice into a project, but these aspects can be limited.

By narrowing the scope of a project, teachers and their students can have short-term success that builds stamina for more complex projects later.

PLAN EARLY

One of the challenges of PBL, but also one of the joys, is the planning process. In PBL, you plan up front, and it does take a significant amount of time. You need to plan assessments and scaffolds and gather resources to support project learning.

While you might be able to do some of this during scheduled planning time, ask your leadership for creative structures to carve out time for planning. Perhaps staff meetings can be used for this time, or release days can be offered.

It’s important to get ahead and feel prepared for and confident about a project. By using the backward design process, you can effectively map out a project that’s ready to go in the classroom.

Once you plan, you’re free to differentiate instruction and meet the needs of your students rather than being in permanent crisis mode trying to figure what will happen tomorrow.

GATHER FEEDBACK

When you have a great project planned, reach out to colleagues both digitally and in person to get feedback. This can be done through posting an idea on Twitter or having a gallery walk of ideas, where teachers walk your project gallery and leave feedback on Post-its. If you’re able, have a 30-minute conversation with a teacher colleague or an instructional coach.

MAIN COURSE, NOT DESSERT

It’s easy in a short-term project to fall into the trap of a “dessert” project that isn’t necessarily inquiry-based. With PBL, the project itself is the learning—it’s the “main course.” In fact, many teachers who think they’re doing PBL are actually doing projects. In PBL you’re teaching through the project—not teaching and then doing the project.

Use an effective PBL project checklist to ensure a high-quality experience while still keeping a narrow focus and timeline. It helps to make sure that you’re focusing on aspects such as inquiry, voice and choice, and significant content.

COMMIT TO REFLECTION

We’re all learners, and when we start something new, we start small, limiting our focus to help us master the bigger thing step by step. A key aspect of this is that when you finish a project, you should carve out time to reflect on it.

Consider journaling, having a dialogue with an instructional coach, or following a structured reflection protocol with a team of teachers.

Through reflection, projects become better and may live on for many years, so that reflection time pays off with time saved on subsequent runs through the project.

Problem-Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning: Six Steps to Design, Implement, and Assess

Twenty-first century skills necessitate the implementation of instruction that allows students to apply course content, take ownership of their learning, use technology meaningfully, and collaborate. Problem-Based Learning (PBL) is one pedagogical approach that might fit in your teaching toolbox.

PBL is a student-centered, inquiry-based instructional model in which learners engage with an authentic, ill-structured problem that requires further research (Jonassen & Hung, 2008). Students identify gaps in their knowledge, conduct research, and apply their learning to develop solutions and present their findings (Barrows, 1996). Through collaboration and inquiry, students can cultivate problem solving (Norman & Schmidt, 1992), metacognitive skills (Gijbels et al., 2005), engagement in learning (Dochy et al., 2003), and intrinsic motivation. Despite PBL’s potential benefits, many instructors lack the confidence or knowledge to utilize it (Ertmer & Simons, 2006; Onyon, 2005). By breaking down the PBL cycle into six steps, you can begin to design, implement, and assess PBL in your own courses.

Step One: Identify Outcomes/Assessments

PBL fits best with process-oriented course outcomes such as collaboration, research, and problem solving. It can help students acquire content or conceptual knowledge, or develop disciplinary habits such as writing or communication. After determining whether your course has learning outcomes that fit with PBL, you will develop formative and summative assessments to measure student learning. Group contracts, self/peer-evaluation forms, learning reflections, writing samples, and rubrics are potential PBL assessments.

Step Two: Design the Scenario

Next you design the PBL scenario with an embedded problem that will emerge through student brainstorming. Think of a real, complex issue related to your course content. It’s seldom difficult to identify lots of problems in our fields; the key is writing a scenario for our students that will elicit the types of thinking, discussion, research, and learning that need to take place to meet the learning outcomes. Scenarios should be motivating, interesting, and generate good discussion. Check out the websites below for examples of PBL problems and scenarios.

Step Three: Introduce PBL

If PBL is new to your students, you can practice with an “easy problem,” such as a scenario about long lines in the dining hall. After grouping students and allowing time to engage in an abbreviated version of PBL, introduce the assignment expectations, rubrics, and timelines. Then let groups read through the scenario(s). You might develop a single scenario and let each group tackle it in their own way, or you could design multiple scenarios addressing a unique problem for each group to discuss and research.

Step Four: Research

PBL research begins with small-group brainstorming sessions where students define the problem and determine what they know about the problem (background knowledge), what they need to learn more about (topics to research), and where they need to look to find data (databases, interviews, etc.). Groups should write the problem as a statement or research question. They will likely need assistance. Think about your own research: without good research questions, the process can be unguided or far too specific. Students should decide upon group roles and assign responsibility for researching topics necessary for them to fully understand their problems. Students then develop an initial hypothesis to “test” as they research a solution. Remember: research questions and hypotheses can change after students find information disconfirming their initial beliefs.

Step Five: Product Performance

After researching, the students create products and presentations that synthesize their research, solutions, and learning. The format of the summative assessment is completely up to you. We treat this step like a research fair. Students find resources to develop background knowledge that informs their understanding, and then they collaboratively present their findings, including one or more viable solutions, as research posters to the class.

Step Six: Assessment

During the PBL assessment step, evaluate the groups’ products and performances. Use rubrics to determine whether students have clearly communicated the problem, background, research methods, solutions (feasible and research-based), and resources, and to decide whether all group members participated meaningfully. You should consider having your students fill out reflections about their learning (including what they’ve learned about the content and the research process) every day, and at the conclusion of the process.

Although we presented PBL as steps, it really functions cyclically. For example, you might teach an economics course and develop a scenario about crowded campus sidewalks. After the groups have read the scenario, they develop initial hypotheses about why the sidewalks are crowded and how to solve the problem. If one group believes they are crowded because they are too narrow and the solution is widening the sidewalks, their subsequent research on the economic and environmental impacts might inform them that sidewalk widening isn’t feasible. They should jump back to step four, discuss another hypothesis, and begin a different research path.

This type of process-oriented, self-directed, and collaborative pedagogical strategy can prepare our students for successful post-undergraduate careers. Is it time to put PBL to work in your courses?

References

Barrows, H.S. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. In L. Wilkerson, & W. H. Gijselaers (Eds.), New directions for teaching and learning,No.68 (pp. 3-11). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Barrows, H.S. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: A brief overview. In L. Wilkerson, & W. H. Gijselaers (Eds.), New directions for teaching and learning,No.68 (pp. 3-11). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dochy, F., Segers, M., Van den Bossche, P., & Gijbels, D. (2003). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis. Learning and instruction, 13(5), 533-568.

Ertmer, P. A., & Simons, K. D. (2006). Jumping the PBL implementation hurdle: Supporting the efforts of K–12 teachers. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 1(1), 5.

Gijbels, D., Dochy, F., Van den Bossche, P., & Segers, M. (2005). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis from the angle of assessment. Review of Educational Research,75(1), 27-61.

Jonassen, D. H., & Hung, W. (2008). All problems are not equal: Implications for problem-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 2(2), 4.

Norman, G. R., & Schmidt, H. G. (1992). The psychological basis of problem-based learning: A review of the evidence. Academic Medicine, 67(9), 557-565.

Onyon, C. (2012). Problem-based learning: A review of the educational and psychological theory. The Clinical Teacher, 9(1), 22-26.

Vincent R. Genareo is a postdoctoral research associate at Iowa State University, Research Institute for Studies of Education (RISE). Renee Lyons is a PhD candidate at Clemson University, Department of Education.

Friday, August 23, 2019

Adaptive Learning

What is Adaptive Learning Anyway?

Published January 11, 2017

By Zach Posner

A look at the science and research behind adaptive learning technology and its application in the classroom.

This post originally appeared on LinkedIn Pulse on January 5, 2017 and can be viewed here.

FUENTE

https://www.mheducation.com/ideas/what-is-adaptive-learning.html.html.html.htm

Learning Objetives

How to write SMART goals and objectives

Specific

You need to be specific. Why? Because your people are going to do what you ask them to do. So you need to be specific about the end result. Use action words like “to increase”, “to establish”, “to reduce” and “to create”.

You can also use “specific” to remind yourself that objectives need to relate back to a specific organisational goal

Measurable

Imagine you are playing a game and it doesn’t show a score or progress indication as you go along. You wouldn’t play it – there’s no motivation!

You want something that will allow the person to gauge how well they are progressing toward achieving the objective. You don’t want an objective that is vague. This leaves room for misinterpretation and that will end in disgruntled people. So tell the person how you are going to measure the achievement. Then you both know when it hasn’t been achieved, when it’s been met and when it’s been exceeded.

For example, ‘100%’, ‘a $ figure’, by 5, etc. A number allows people to see if they have achieved the goal.

It’s also a good idea to record the source of the measurement. For example, the profit & loss report for retail division, client survey, sales reports.

Attainable

Stretch goals can be motivating, but if they are too much of a stretch they won’t be achieved. Goals need to stretch a person to give them a sense of achievement, but they also need to be attainable.

If a goal is too hard, a person will either give up before they start or put in the effort only to end in disappointment. If a goal is too easy, it won’t provide a sense of achievement. A good goal needs to have just the right level of stretch

Relevant

Is the objective within something the person will have control or influence over? The answer to this question must be “yes” if you want the objective to be achieved. Setting an objective for a person that involves something they can’t control or influence is unfair and will lead to disgruntlement.

It’s also a great idea to think of “R” as relate. Relate the objective back to the team and company goals. Being part of a team effort is much more motivating than just having an objective.

Time-bound

SMART goals have a time frame in which they need to be achieved. If you set a goal without a target date it is unlikely to be achieved. Along with a target date it’s also a good idea to define milestones. This helps you gauge progress and identify problems early enough for them to be solved

Fuente

Instructional Systems Design

What is ISD?

by Karen L. Medsker, Ph.D.

Instructional Systems Design:

ISD Models

- Large numbers of learners must be trained.

- A long lifetime is expected for the program.

- Standard training requirements must be maintained.

- High mastery levels are required because of criticality, such as safety or high cost of errors.

- Economic value is placed on learners' time.

- Training is valued in the organizational culture.

Fuente

http://www.hpsi.bz/HPSI_ISD_article.htmlRapid Learning Model

How Rapid eLearning Development Provides Additional Value to an eLearning Project

Fuente

https://elearningindustry.com/how-rapid-elearning-development-provides-additional-value-to-an-elearning-project

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Gamification

FUENTE: EDX.ORG Educational software Knewton has produced a visually-appealing infographic on gamification:

-

Problem-Based Learning: Six Steps to Design, Implement, and Assess By: Vincent R. Genareo PhD and Renee Lyons FUENTE: https://www....

-

Getting Started With Project-Based Learning (Hint: Don’t Go Crazy) A handful of tips to help teachers ease into PBL without getting over...